Rachel Joynt

Designs on natural history

While Rachel Joynt’s successful public sculptures are eminently legible, their enduring appeal stems from their detail and scale, writes Lisa Godson.

In terms of public commissions, Rachel Joynt is one of the most successful sculptors of her generation. The Kerry-born sculptor lives and works far from the city, far from the sea, in the foothills of the Blackstairs Mountains in Co Carlo w (Fig 2). She says that it is here, in this ‘arcadian landscape’ that she finds the stillness and spaciousness to develop her projects. These are orientated in two key directions – horizontal along the ground plane, and vertical against the sky.

Even before she had graduated from NCAD in 1989, her work had appeared on the streets of Dublin, albeit in a less obtrusive form than her more large-scale practice. In her third year as a sculpture student, Joynt’s People’s Island was installed on the traffic island between Westmoreland Street and O’Connell Bridge (Fig 3), the winning entry of a competition organized by the Sculpture Society of Ireland (SSI). Although the SSI had removed it from the list of possible sites for being ‘too busy’ it was the hustle of this ‘inbetween’ space that appealed to Joynt. Set in the hard paving core are concrete, bronze and brass casts of shoe soles, and the tracks of footprints and birds’ feet. The ground-level setting of this charming piece is one axis Joynt subsequently followed, a practice whereby her work is literally stumbled upon and acts almost as a visual echo or palimpsest.

Take another work from that period: the plaques set in the pavement around Wood Quay, the former Viking site in Dublin.These feature bronze replications of artifacts found in the hugely important archaeology dig of the late 1970s.They materialize a fragmented memory of an entire culture, its discovery through these objects, their recovery and the erasure of their original setting by time and bulldozers. Given the controversial building of the Civic Offices on this most significant historical site, Joynt’s recreation of the tools and products of the silver-smiths and comb-makers that occupied the area almost a millennium ago are a strike for memory against the brutal forgetfulness of the planners of modern Dublin.

The trace of history is echoed in other work: through form, material, meaning and setting. Starboard (2001) alongside the river Lagan in Belfast describes the shape of a ship’s plan in transluscent blue cobbles set in an iron grid, a reference to the metal cellar covers almost unseen on city streets. For this, Joynt studied aerial maps of the old graving docks where the piece appears and where the skeletal outline of a ship-in-progress was evident. Working with similar materials in a similar setting, her Free Flow (2006) follows one kilometer of paving along the Liffey towards the sea from the Customs House Quay to the Point Depot on the northside of Dublin’s Docklands. It comprises 900 transluscent glass cobbles cast in shades of green and blue, created in collaboration with glass artist Killian Schurmann (Fig 1). These are lit from underneath and have delicate little silver and copper fish suspended inside. The nature of the different materials offers a variety of light effects, the glow of the cobbles moved by the glint from the fish. Joynt has said she wants the cobbles to ‘suggest windows on an underwater world’ and their meandering placement draws attention not only to the movement of everything towards the sea, but also the severely contained course of the river alongside.

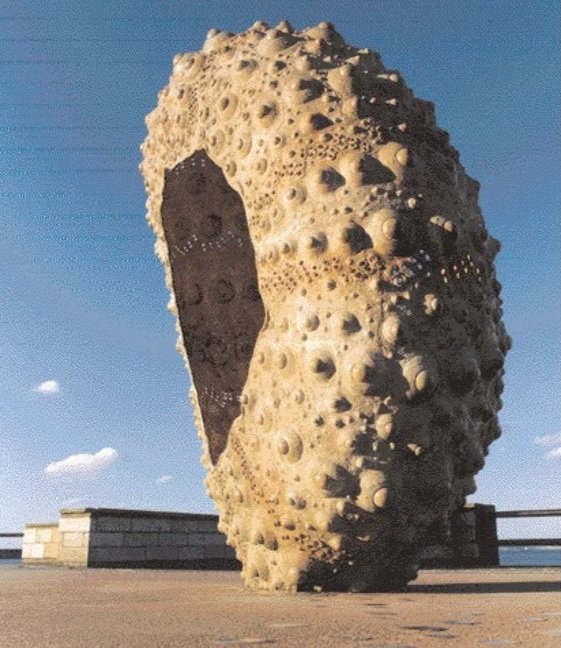

Joynt attributes her success at winning public commissions to her response to site, explaining that she approaches each project with a completely ‘fresh eye.’ It is also because her work seems relatively ‘legible’: often derived from natural forms with a clear link to location. This connection is often worked out in detail, for example, Mothership (1999) sited at Sandycove in south Dublin (Fig 4). Joynt describes this as ‘a giant sea urchin that has just rolled out of the sea’, with the traces of its movement echoed in metal droplets on the pavement at its base. This was originally funded by the engineers of a new sewage system, involving a giant pipe-line under ground, two metres in diameter. Although maybe not a conventional starting point for traditional sculpture, Joynt reflected this sponsorship in the dimensions of the sculpture and her choice of a sea urchin as representative of clean seas, the holes in its shell like a filtration system. With this as with other work, Joynt attributes her achievement partly to her collaboration with skilled technicians, such as the foundry that managed to cast the bronze of the sea urchin in a depth of only six millimeters, ensuring, as Joynt says, ‘a tension’ between the fragility of its pierced form and its massive scale.

Joynt expresses a sense of delight and fascination with the very particular form of the sea urchin and the other natural forms she drew on for her giant starfish Guiding Star (2009), Mother of Pearl (Fig 8) and the sperms that teem over Noah’s Egg (2004). All reflect her meticulous research and another form of collaboration, with scientists. For Mothership she studied sea urchin shells in the Natural History Museum, and worked with a Paleontologist in Trinity College Dublin who could provide her with images of the sea urchin’s structure magnified up to forty times.

For Noah’s Egg (Fig 5) she worked with an embryologist to study the sperm of a range of creatures including humans, birds, rabbits and hamsters. Joynt modeled these forms to swarm over the surface of a giant bronze ovoid, sited on top of a small hill on the UCD campus in Belfield. Located beside the Faculty of Veterinary, Joynt describes her choice of an egg as ‘a universal image of life and potential relating not only to the veterinary department but the University with so many young people starting out.’ While Noah’s Ark’s siting and clear, simple form has a strong presence at a distance, up-close it conjures with perceptions of scale. The pointed end of the egg has an eye piece built into it, and peering through it, the effect is akin to a clear night sky (Fig 5) the surface is perforated with tiny holes, making pricks of light on the interior. This sense of the cosmos contained within one simple form gives resonance to Joynt’s statement that with her work, a ‘sense of discovery is paramount.’ She explains ‘I don’t want a sign telling people what to do’ and delights in the way people interact with her work.

As a maker of public sculpture, Joynt observes that she has a ‘nervewracking responsibility.’ Although her works are meticulously researched and she is ‘caught up in every little detail’, when they are completed she has to ‘walk away: it is not mine anymore.’ Observing Mothership on a wintry day in Sandycove, the transference from artist to public is palpable – two children run up to the giant sea urchin, one climbing inside while the other bangs on the outside with a stick, couples take each other’s photograph standing beside it, and someone pats it as they walk past.

Joynt characterises her large-scale sea sculptures such as Mothership and Guiding Star at Clogher Head as appearing as if they ‘have been magically tossed up or rolled in from the sea’ and in some sense she is like a midwife helping birth these amazing creatures and then setting them down to be wondered at and enjoyed: ‘I want to make visible these hidden forms and raise them from the sea to a more crystallised conscious expression’. So not only with Noah’s Ark with its built-in invitation to explore through the eye-piece, but all her work she is concerned with how it might both interest and speak to the public. Guiding Star is set on the pier at Clogher Head, a fishing village in Co Louth (Figs 6&7). A two-ton starfish in patinated cast iron in a reference to its harbour setting, it not only relates to its setting by the sea but also the way sailors traditionally used stars to steer by.

As with most of her work, Guiding Star is layered – although apparently just a giant version of a starfish, it resonates with its setting with a hardwon rightness, not only relating to but reaffirming place and locale. It is this combination, this balancing trick of finding what seems the most appropriate and legible form for a specific place yet leaving it open for individual encounter that most characterises her work. Although her sculptures are recognisable in being representations, they are still surprising in their detail and scale. She says ‘for me, a successful public artwork needs to have a sense of place, a freshness, some intrigue and playfulness, a bit like a frozen moment from a daydream.'